Пасхальное яйцо – один из самых узнаваемых символов праздника. Традиция дарения августейшими особами яиц на Пасху существует в России давно и известна еще со временем первых Романовых. Яйца были как натуральные – от куриных и лебединых до гусиных и голубиных, так и искусственные – от деревянных и костяных до каменных и металлических. А первое известное нам фарфоровое яйцо было подарено в 1749 году основателем Императорского фарфорового завода и изобретателем русского фарфора Дмитрием Виноградовым императрице Елизавете Петровне. С этого момента вплоть до 1917 года Императорский фарфоровый завод выпускал пасхальные яйца для императора и членов его семьи «на раздачу» при христосовании.

Поскольку фарфоровая масса была дорогим и редким материалом, завод изготавливал пасхальные яйца исключительно для нужд царского двора. Выполненные из хрупкого фарфора, покрытые миниатюрной живописью и позолотой, яйца были не только дорогим императорским пасхальным подарком, но и разновидностью награды за службу, своеобразным знаком внимания приближенным на юбилейные даты и свадебные торжества.

Все яйца имеют сквозное отверстие. Через него пропускалась специально подобранная по цвету и композиции муаровая лента. Она завязывалась бантом внизу и петлей вверху. Яйца с лентой подвешивались в красный угол, под иконы. Для завязывания лент нанимали «бантовщиц» – нуждающихся вдов и дочерей работников Императорского фарфорового завода. Такая работа хорошо оплачивалась и носила благотворительный характер.

Коллекция пасхальных фарфоровых и стеклянных яиц – одна из значительных в собрании Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль». Ее формирование началось в 2009 году с приобретения фарфоровых яиц в антикварном салоне. Сегодня коллекция насчитывает 32 предмета, изготовленных в ХІХ – начале ХХ века на Императорском фарфоровом и частных заводах России.

Яйцо пасхальное, декорированное рельефной резьбой с изображением Николая Чудотворца и сюжета «Сошествие во ад».

Императорский стеклянный завод, начало XX в.

Стекло, формовка, резьба, полировка. Из собрания Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль».

Императорский стеклянный завод (1777) – одно из старейших в России предприятий, специализировавшееся на выпуске изделий из стекла. В конце XIX в. завод стал частью другого Императорского завода – фарфорового.

В коллекции Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль» хранится яйцо из толстостенного прозрачного стекла с оттенком зелёного цвета, декорированное выемчатой рельефной резьбой с изображениями Николая Чудотворца и сюжета «Воскресение Христово – Сошествие во ад».

На оборотной стороне – Иисус Христос, спустившийся после смерти на кресте в ад. Ногами Христос попирает врата ада. Справа и слева от него – Адам, Ева и пророки, которых Иисус выводит из преисподней.

Святитель Николай представлен с митрой – головным убором, частью богослужебного облачения епископа, с благословляющим жестом правой руки и Священным Писанием в левой.

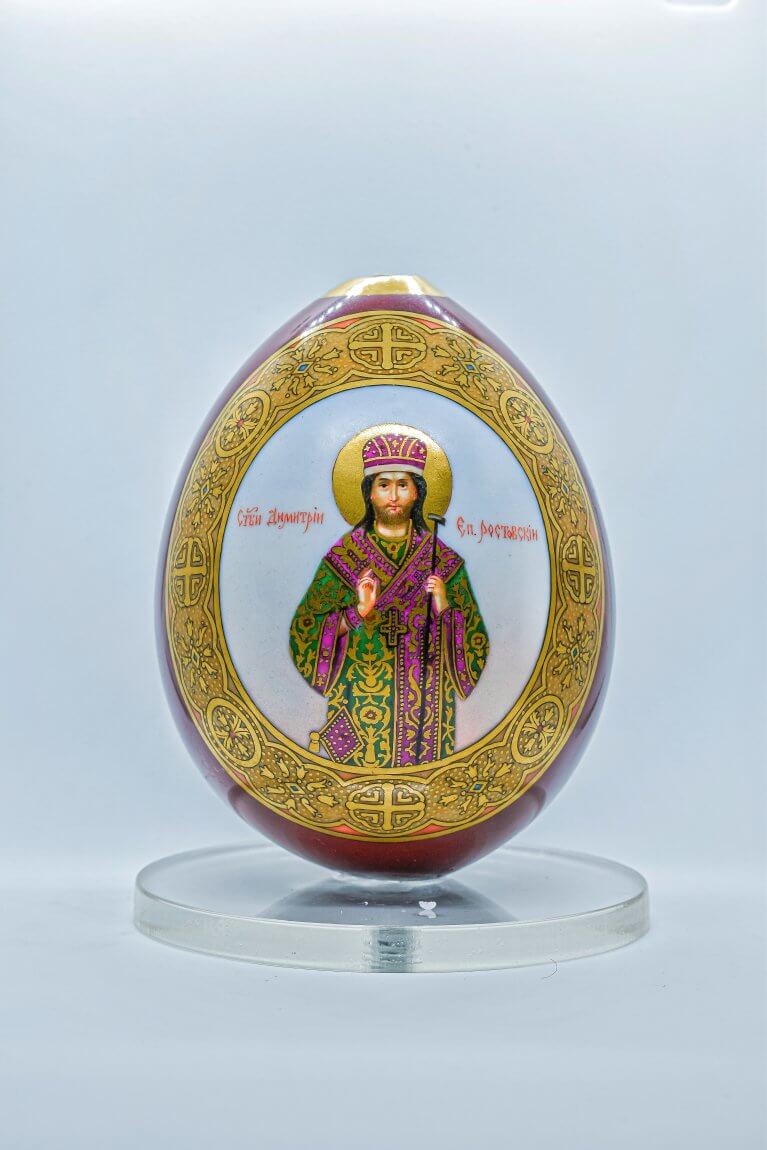

Яйцо пасхальное с образом святого Дмитрия Ростовского по эскизу О.С. Чирикова. Императорский фарфоровый завод, Санкт-Петербург, 1887 – 1890-ые гг. Фарфор, крытье цветное надглазурное, роспись надглазурная полихромная, позолота. Из собрания Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль».

Яйцо с образом святителя Димитрия Ростовского, предположительно, созданное по эскизам Осипа Чирикова.

Осип (Иосиф) Семёнович Чириков – русский художник-иконописец и реставратор из села Мстёры (Владимирская область).

Димитрий Ростовский – епископ Русской православной церкви, митрополит Ростовский и Ярославский; духовный писатель, проповедник, педагог, автор известного сборника «Книга житий святых», куда вошли жития и первых казанских святителей Гурия, Германа и Варсонофия.

На яйце святой Димитрий изображен в узорчатом зеленом саккосе (верхнее архиерейское богослужебное облачение) с бордовым омофором (широкая лента) и в митре (головной убор епископа). Правая рука святого поднята в благословляющем жесте, а левая держит епископский посох. Рядом написано: «Святой Димитрий еп(ископ) Ростовский». Вокруг миниатюры – овальная рамка с золочёным узором из розеток и крестов. С другой стороны, на кирпично-красном фоне – орнаментированный крест.

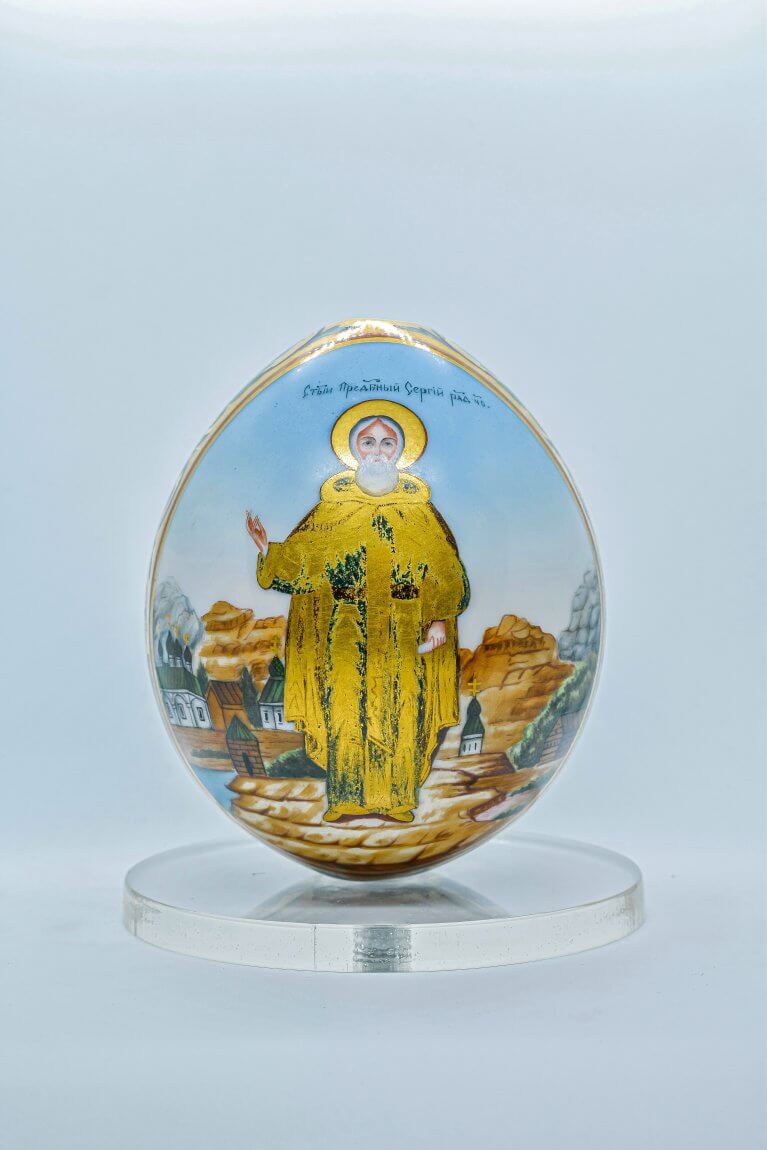

Яйцо пасхальное с образом Сергия Радонежского по эскизу О.С. Чирикова, орнамент по проекту А.С. Каминского. Императорский фарфоровый завод, Санкт-Петербург, 1890-ые гг.

Фарфор, роспись надглазурная полихромная, позолота. Из собрания Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль».

Яйцо с образом Сергия Радонежского создано по эскизу из серии «живописи святых и двунадесятых праздников», созданных Осипом Чириковым в 1887 году, специально для росписи фарфоровых пасхальных яиц, выпускавшихся ограниченным тиражом только по заказам императорской семьи.

Сергий Радонежский – игумен Русской церкви, основатель Троице-Сергиевой лавры, один из самых почитаемых христианских святых.

На фарфоровом яйце Преподобный Сергий изображен в полный рост на фоне церквей и зданий Троице-Сергиевой Лавры. Правая рука сложена в благословляющий жест, левая – держит свиток. Над его головой надпись: «Святой Преподобный Сергий Радонежский чудотворец».

На другой стороне яйца – орнаментированный равноконечный крест с изображением Богоматери в центре, а также золочёные звёзды и орнаменты. Она выполнена по проекту русского архитектора, автора первого здания Третьяковской галереи и Третьяковского проезда – Александра Степановича Каминского.

Аналоги данного яйца хранятся в Государственном историческом музее в Москве и Музее Императорского фарфорового завода в Санкт-Петербурге.

Яйцо пасхальное с изображением миниатюры «Преображение Господне на горе Фавор».

Императорский фарфоровый завод, Санкт-Петербург, середина XIX в.

Фарфор, крытье надглазурное, роспись надглазурная полихромная, золочение, цировка по золоту. Из собрания Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль».

Пасхальное фарфоровое яйцо с Библейским сюжетом, описанным в Евангелиях от Матфея, от Марка и от Луки – Преображение. Христос с тремя ближайшими учениками: Петром, Иаковом и Иоанном (на яйце они изображены в цветных одеждах у основания) поднялся на гору помолиться. На горе Иисус преобразился перед ними – Его лицо просияло, как солнце, а одежды стали белыми как свет. Появились пророки Моисей и Илия – на яйце они изображены справа и слева от Иисуса в таких же белоснежных одеждах, как и у Христа.

На обратной стороне яйца в центре композиции изображен Крест, на котором был распят Христос. Слева от Креста – скрижали – плиты, на которых были записаны 10 Божьих заповедей, они олицетворяют Ветхий Завет. Справа от Креста – книга – Евангелие, олицетворяющее Новый Завет. Таким образом, Крест – это связь между двумя заветами, между Богом и человеком.

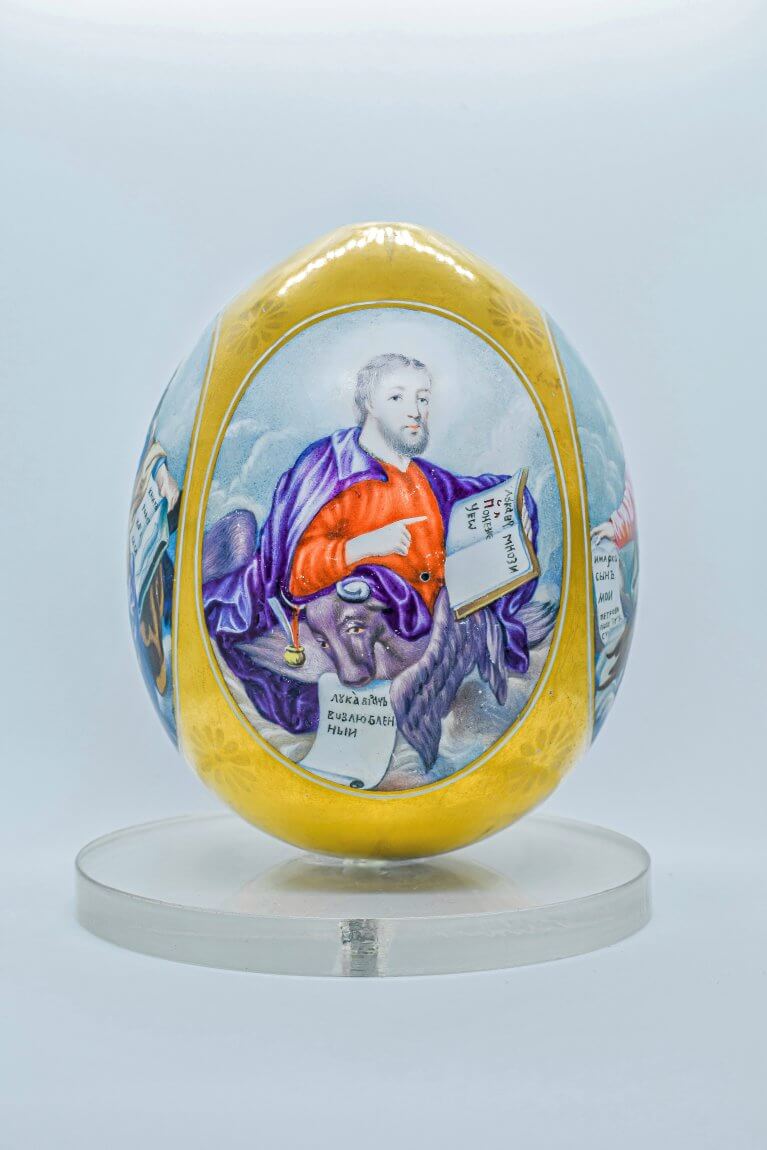

Яйцо пасхальное с изображением четырех евангелистов

Императорский фарфоровый завод, Санкт-Петербург, 1851 – 1900 гг.

Фарфор, роспись надглазурная полихромная, позолота, цировка. Из собрания Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль».

Пасхальное яйцо с изображением четырёх евангелистов – апостолов, авторов четырёх канонических Евангелий: Матфея, Марка, Луки и Иоанна. Рядом с ними изображены тетраморфы – существа, символизирующие каждого из евангелистов.

Матфей изображен с Ангелом. В его книге – начало Евангелия от Матфея: «Книга родства Иисуса Христа».

Марк изображен со львом. В его лапах книга с началом Евангелия от Марка: «Зачало Евангелия Иисуса Христа, Сына Божия».

Лука изображен с тельцом. В книге – начало Евангелия от Луки: «Понеже убомнози…»

Иоанн изображен с орлом. В книге – начало Евангелия от Иоанна: «В начале бе Слово, и Слово бе…»

Яйцо пасхальное с изображением панорамы Александро-Невского Ново-Тихвинского монастыря в Екатеринбурге.

Императорский фарфоровый завод, Санкт-Петербург, конец XIX – начало XX века.

Фарфор, роспись надглазурная, позолота. Из собрания Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль».

С лицевой стороны яйца изображена панорама Александро-Невского Ново-Тихвинского монастыря – женского православного монастыря в Екатеринбурге, одного из крупнейших в России. Монастырь ведёт свою историю с конца XVIII века.

На обратной стороне изображен потир – сосуд для христианского богослужения, в котором во время главного православного богослужения литургии, хлеб и вино претворяются в тело и кровь Христа.

Потир «вырастает» из якоря – распространённого христианского символа надежды и непоколебимости. Якорь олицетворяет Христа, дающего безопасность и спасение в бушующем море жизни.

Яйцо пасхальное с букетом роз по эскизу К.Н. Красовского (?).

Императорский фарфоровый завод, Санкт-Петербург, середина XIX в. Фарфор, роспись надглазурная, золочение. Из собрания Музея-заповедника «Казанский Кремль».

Константин Николаевич Красовский – мастер Императорского фарфорового завода. Был лучшим учеником приглашенного на завод французского художника Петра Буде – виртуозного мастера живописи фруктов, цветов, насекомых и орнаментов. В 1864 г. Академией Художеств ему было присвоено звание «свободного художника» живописи цветов и плодов на фарфоре.

Здесь представлено, вероятно, одно из яиц, расписанных по эскизу Константина Красовского кобальтового (ярко-синего) цвета. С одной стороны на нём изображён полихромный букет цветов, с другой – резерв с золочёными цветами и листьями, обрамлённый рокайльным орнаментом.

Популярность фарфоровых яиц Императорского завода была невероятно велика, но выпускались они в ограниченном количестве. С увеличением количества заказов на эти предметы изготовление наиболее простых с орнаментами и «цветочной живописью» стали передавать на частные заводы, которые стали производить более демократичные аналоги, копируя императорскую продукцию. По своему качеству такие яйца были близки к продукции Императорского фарфорового завода, однако мало кому удавалось достичь уровня мастерства императорских миниатюристов.