Процесс заселения кремлевского холма начался еще в глубокой древности.

История Казанского Кремля охватывает более тысячи лет и несколько исторических этапов.

Процесс заселения кремлевского холма начался еще в глубокой древности. Наиболее ранние находки, обнаруженные на этой территории, относятся к эпохе мезолита. Первых людей привлекали природно-географические условия. Кремлевский холм в свое время был с трех сторон окружен водой: с востока он был обрамлен цепью озер, впадающих в реку Казанку, омывающую холм с севера; с запада и юго-запада крепость защищала илистая протока Булак. Строительство укрепленного поселения на Кремлевском холме, на основе которого и выросла современная Казань, связана с государством Волжская Булгария.

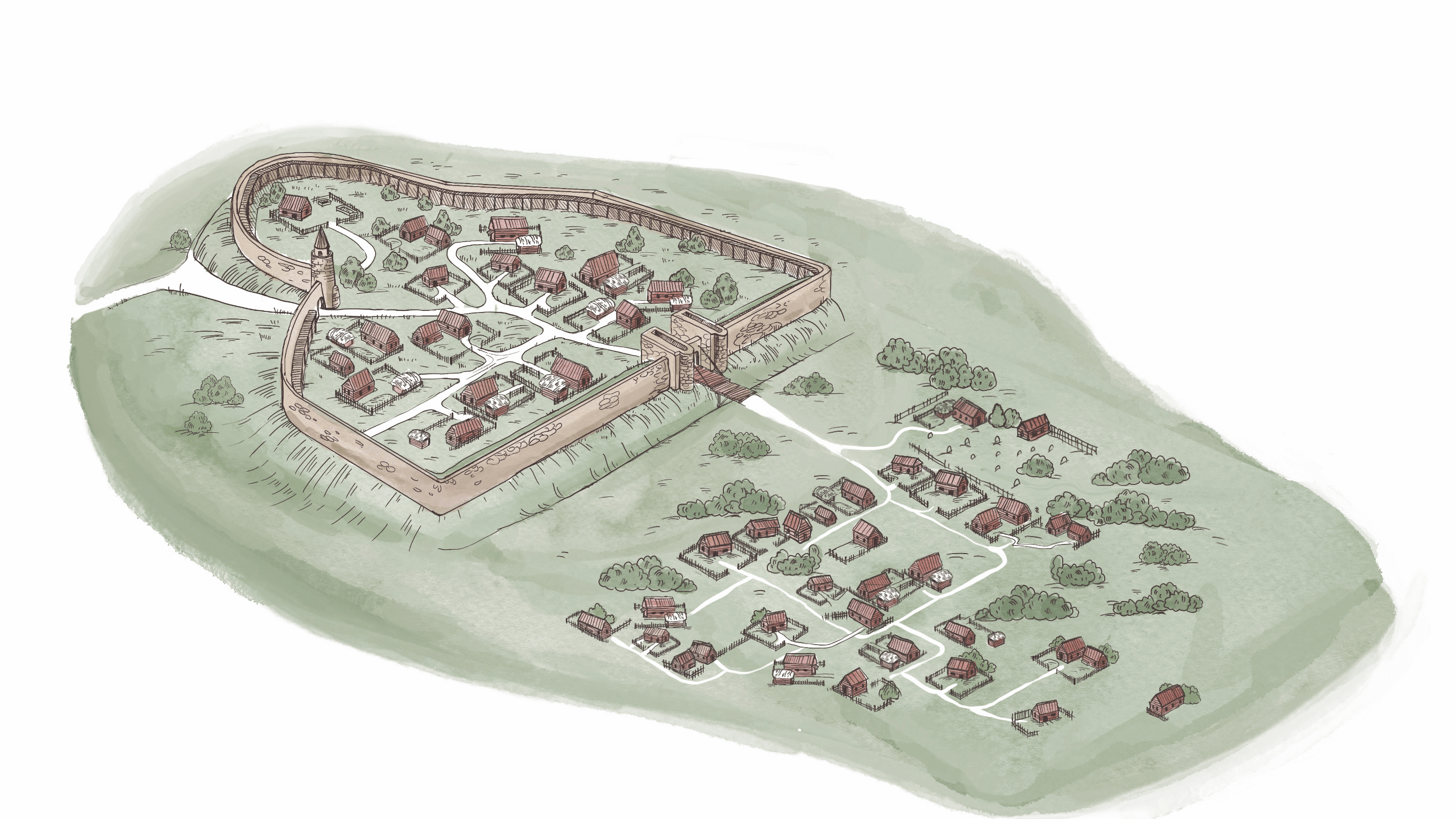

Возведение укреплений начинается с северной оконечности кремлевского холма и относится к рубежу Х-ХI веков.

Булгары появились в бассейне реки Казанки на рубеже IX – X веков. К рубежу X – XI веков они освоили Кремлевский холм, возведя с южной его стороны мощную линию укреплений, состоявшую из крутого рва-оврага и земляного вала с проездными воротами. С восточной и северной стороны располагался частокол бревен с заостренными обожженными концами.

Постепенно крепость обросла посадом, здесь возникло ремесло, торговля, а к началу XII века сформировался самостоятельный город. Усиление роли Волжской Булгарии в регионе и военные набеги русских княжеств повлияли на дальнейшее развитие Казани. В этот период на месте прежних деревянных укреплений создаются мощные белокаменные стены, которые просуществовали до эпохи Казанского ханства. В XII – первой половине XIII века Казань сохраняла значение форпоста северо-западных границ Волжской Булгарии и торгового центра.

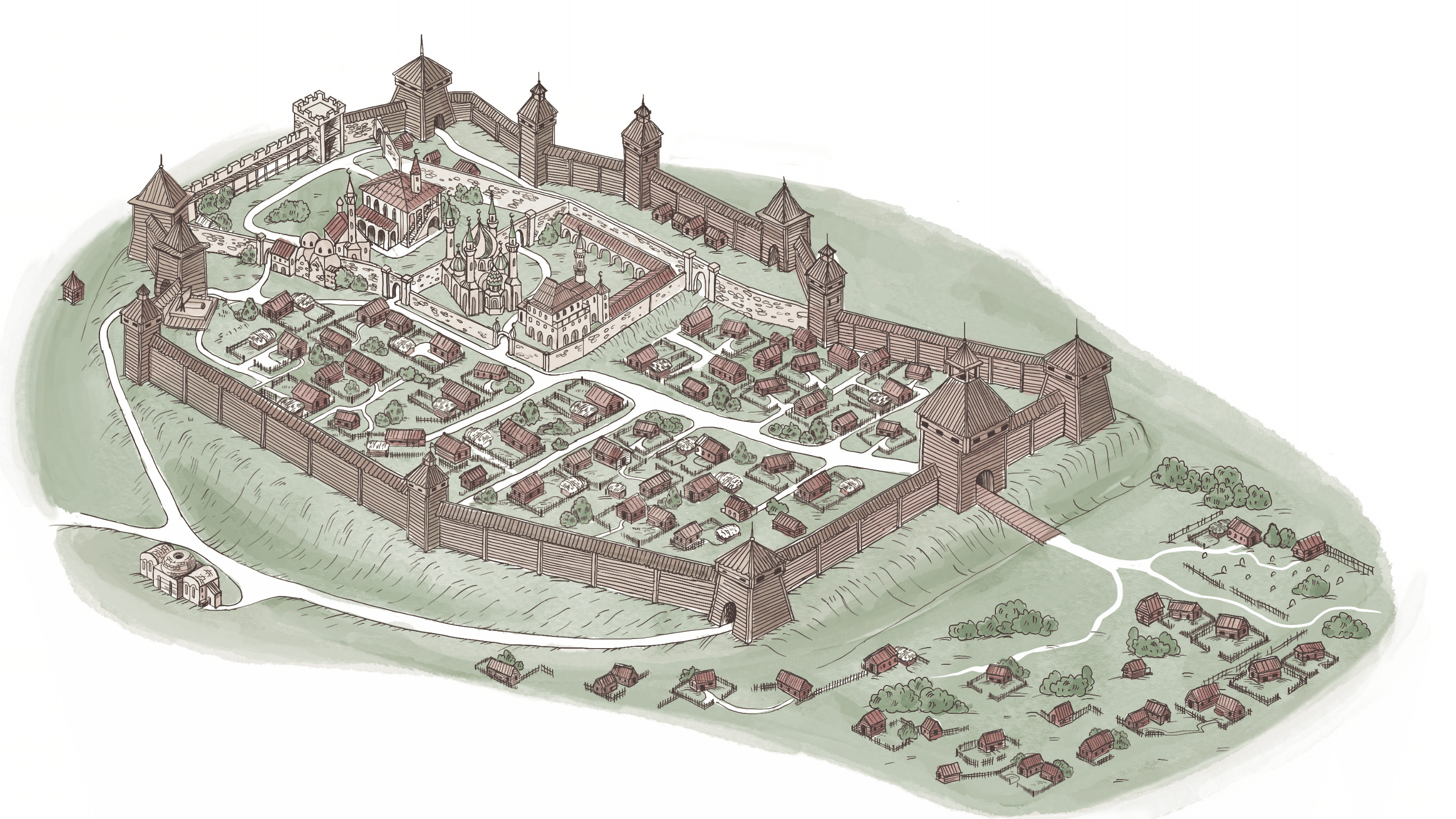

В середине XV века, после распада Золотой Орды, Казань становится административным центром государства, получившего в исторической литературе название «Казанское ханство» и просуществовавшего с 1438 по 1552 годы.

После того, как Волжская Булгария вошла в состав Золотой Орды в 1220–1240-х годах, Казань из небольшой пограничной булгарской крепости, преимущественно с военно-торговыми функциями на периферии Волжской Болгарии превратилась в достаточно крупный региональный центр.

В середине XV века прежние укрепления по восточному и северному склону прекратили свое существование, однако в период Казанского ханства эта часть стены была восстановлена. Южная линия укреплений продолжала функционировать без значительных изменений также до середины XV века. Ров с этой стороны также сохранялся, но его глубина значительно уменьшилась.

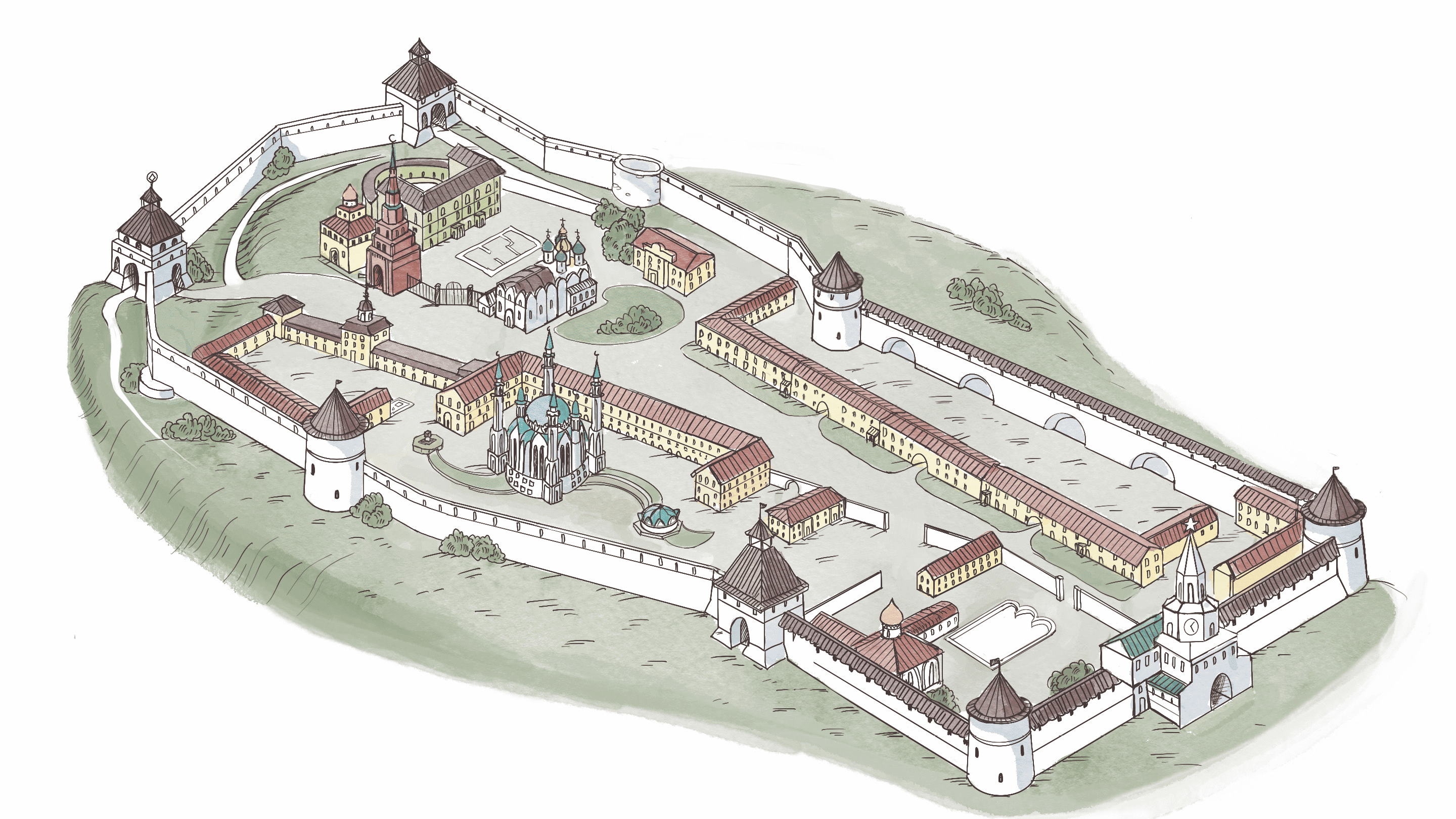

После распада Золотой Орды здесь образовалось Казанское ханство, просуществовавшее с 1438 по 1552 годы. Казань стала его административным центром. В этот период казанская крепость вышла за пределы прежних укреплений. Внутри крепости происходило уплотнение застройки, появились ханский двор и кирпично-каменные здания: ханский дворец, соборная и ханская мечети, ханские мавзолеи. Казань эпохи Казанского ханства представляла собой крупный торговый и ремесленный средневековый город с высоким уровнем развития культуры и просвещения, где мирно жили представители разных народов и религий.

Возросшая геополитическая роль Казани, как оплота русского государства в Поволжье, показала необходимость расширения и укрепления её защитных сооружений.

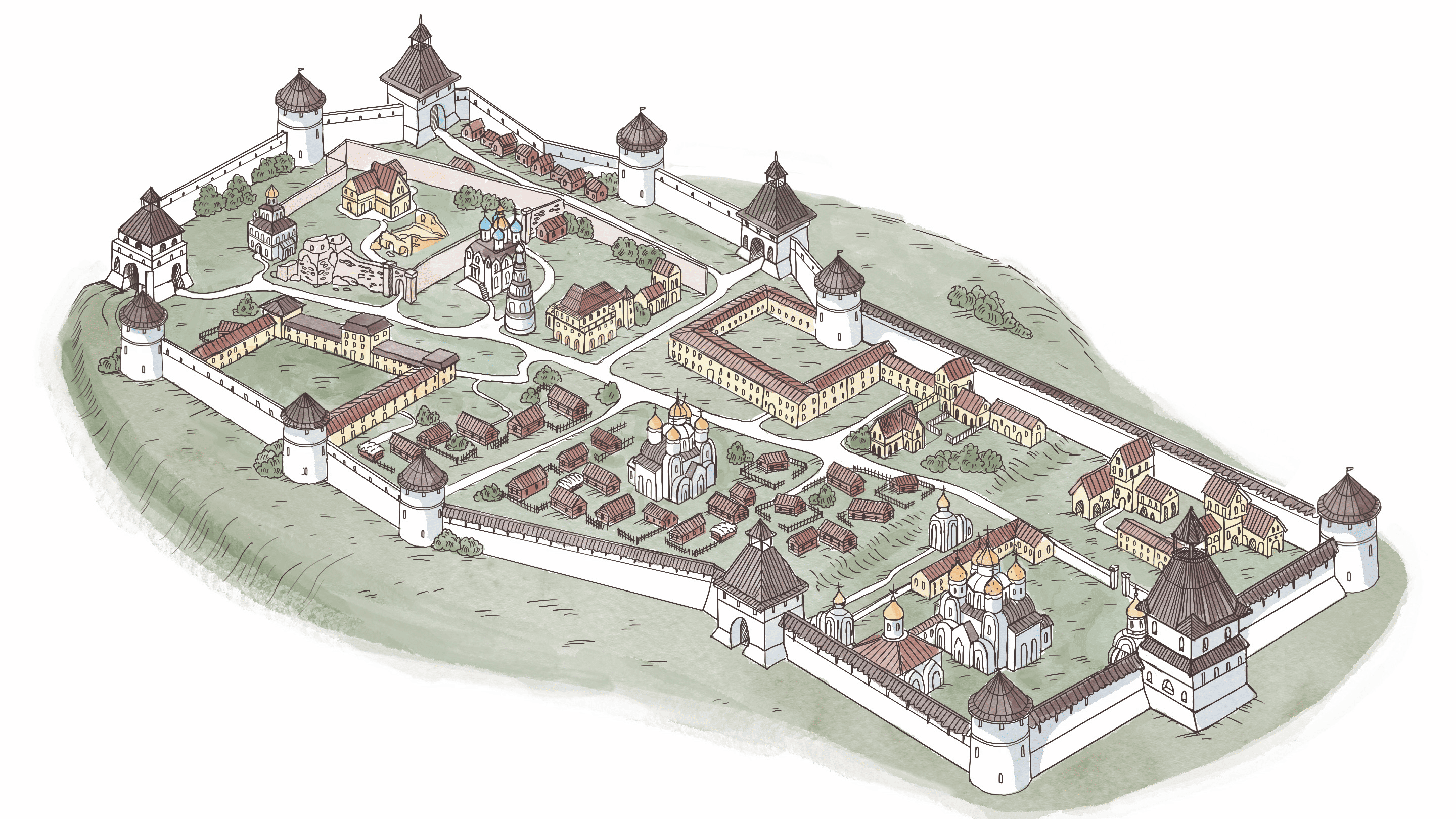

В 1552 году Казанское ханство вошло в состав Российского царства. Возросшая геополитическая роль Казани, как оплота русского государства в Поволжье, показала необходимость расширения и укрепления её защитных сооружений. По поручению Ивана Грозного в 1556–1562 годах в Казань для строительства нового белокаменного Кремля были направлены знаменитые псковские зодчие Постник Яковлев и Иван Ширяй. Под их руководством на месте старой крепости возводили новую систему укреплений из 13 башен и крепостных стен. Новый Казанский Кремль был расширен в южном направлении. К началу XVII века его границы окончательно сформировались и дошли до настоящего времени.

Помимо оборонительных сооружений псковские мастера на территории Казанского Кремля построили первые православные храмы: Благовещенский собор и церковь Киприана и Устиньи. Были основаны Троице-Сергиев и Спасо-Преображенский монастыри.

Долгое время сохранялись постройки ханского периода: ханская мечеть, ханский дворец и мавзолеи использовались для хранения оружия и боеприпасов, однако в итоге строения были разобраны.

В XVII веке в западной части Казанского кремля на месте бывшей ханской гвардии был создан Пушечный двор, где осуществлялся ремонт и производство оружия.

В конце XVII – начале XVIII века была построена башня Сююмбике, выполнявшая функцию дозорной башни.

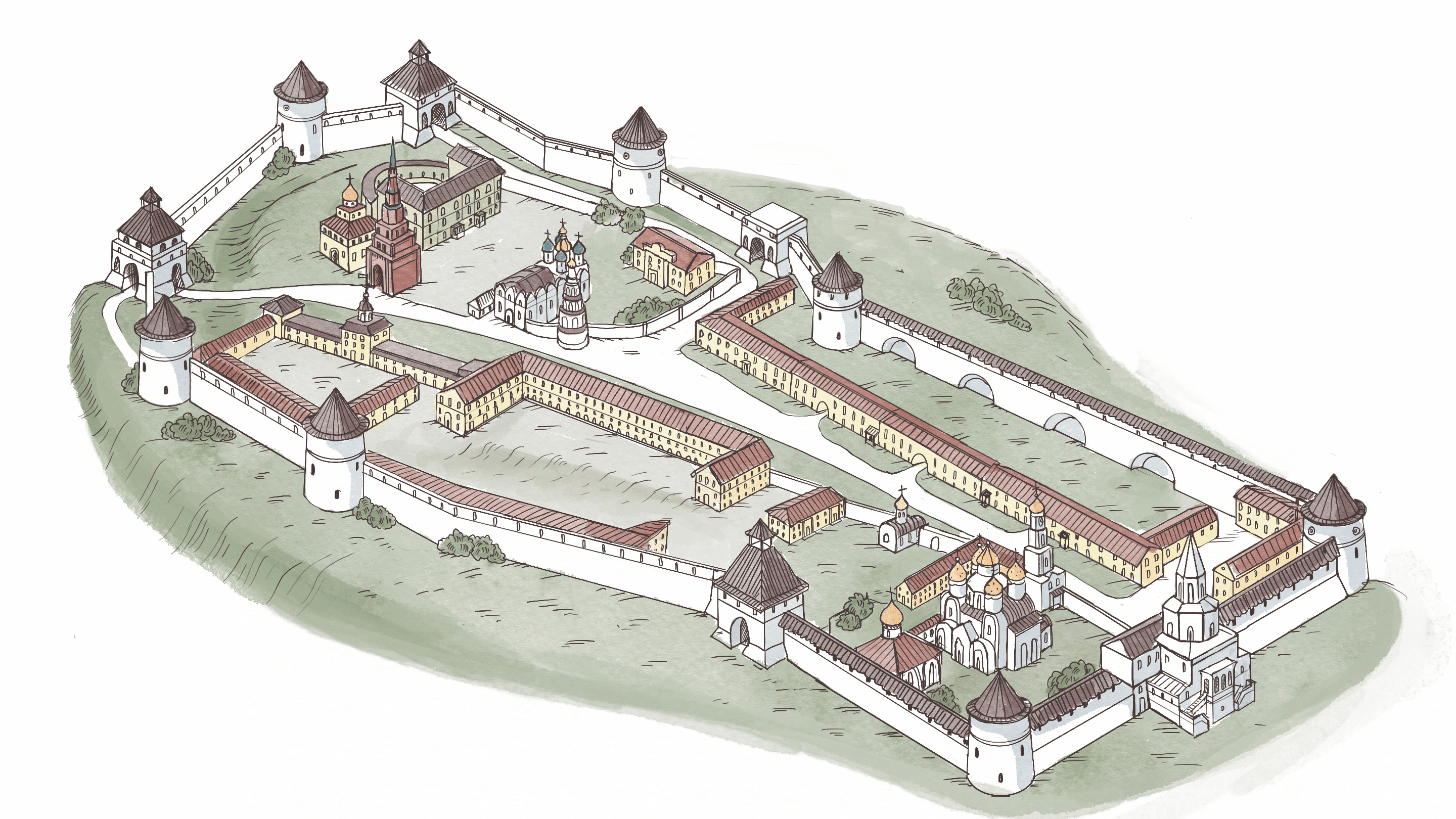

В 1708 году была образована Казанская губерния, что повлекло за собой строительства во второй половине XVIII века здания Присутственных мест, предназначавшегося для работы государственных служащих.

В 1848 году по поручению Николая I был построен Губернаторский дворец, где размещались императорские квартиры, губернаторские комнаты и помещения для придворных служителей. В XIX веке на территории Казанского Кремля также были построены здания юнкерского училища, духовной консистории и новый архиерейский дом. Архитектурный ансамбль Казанского Кремля, окончательно сложившийся к середине XIX века, по большей части сохранил свой исторический облик и в значительной степени дошел до наших дней.

В период Великой Отечественной войны Казань стала местом эвакуации мирных жителей, заводов и техники из западных регионов страны. Город принял более 70 эвакуированных предприятий Советского Союза, а население города увеличилось к 1942 году с 401 до 515 тысяч человек.

В советский период Казанский Кремль стал административным центром ТАССР. В результате масштабной антирелигиозной деятельности были разрушены колокольня и соборный храм Спасо-Преображенского монастыря, колокольня Благовещенского собора, церковь святых Киприана и Иустинии, часовня при Спасской башне, утрачены православные реликвии.

В период Великой Отечественной войны Казань стала местом эвакуации мирных жителей, заводов и техники из западных регионов страны. В связи с этим часть территории и строений Казанского Кремля предоставили под расселение рабочих московского завода №22 авиационной промышленности СССР. В Кремле в это время помимо зданий административного назначения находились квартиры, детский сад, общежитие, танковое училище и столовая. За годы войны Казанскому Кремлю был нанесён большой урон: здания, отданные под общежития и квартиры, находились в аварийном состоянии, частично обрушились кремлевские стены и башни. Во второй половине 1940-х и в 1950-е годы шли работы по точечному ремонту зданий, элементов архитектуры и благоустройству территории Кремля. Полномасштабная систематическая реставрация объектов Казанского Кремля в данный период не велась.

22 января 1994 года указом первого президента Республики Татарстан М.Ш. Шаймиева был создан Музей-заповедник «Казанский Кремль».

В 1993-1994 годах в целях проведения реставрационных работ под руководством архитектора С.С. Айдарова и историка-археолога А.Х. Халикова был разработан документ «Основные направления научной концепции сохранения, реставрации и использования ансамбля Казанского Кремля и первоочередных мероприятий и по ее реализации». Этот документ определил проведение археологических исследований и реставрационных работ.

22 января 1994 года указом первого президента Республики Татарстан М.Ш. Шаймиева был создан Музей-заповедник «Казанский Кремль». Его первым директором стал Ильдус Вахитов. Уже на территории музея-заповедника были восстановлены 9 башен и стены, 4 башни были законсервированы и музеефицированы, полностью отреставрировано здание Резиденции Раиса РТ, а большая часть территории Кремля изучена археологами. В результате проведенных реставрационных работ был укреплен фундамент башни Сююмбике, музеефицированы ханский дворец, ханская мечеть и усыпальница казанских ханов, возведен мавзолей для перезахоронения останков казанских ханов, которые были обнаружены во время археологических раскопок. Были отреставрированы здания комплекса Пушечного двора и открыт Благовещенский собор.

В 1995 году начались работы по возведению мечети Кул Шариф. Она была торжественно открыта 24 июня 2005 года, к 1000-летию Казани.

В 2000 году историко-архитектурный комплекс Казанского Кремля был включен в Список всемирного культурного и природного наследия ЮНЕСКО.

В 2022 году в здании Присутственных мест появилось новое выставочное пространство. В 2023 году в Музее-заповеднике «Казанский Кремль» открылся Музей Спасской башни. Тогда же на Спасской башне запустили реконструкцию «малинового звона» 1967 года конструкторского бюро «Прометей». Впервые с XVI века Спасская башня стала открытой для посещения. На сегодняшний день Казанский Кремль является одним из самых популярных туристических объектов России, который ежегодно посещают более 4 миллионов человек.